Talkin' With Bill Payne of Little Feat

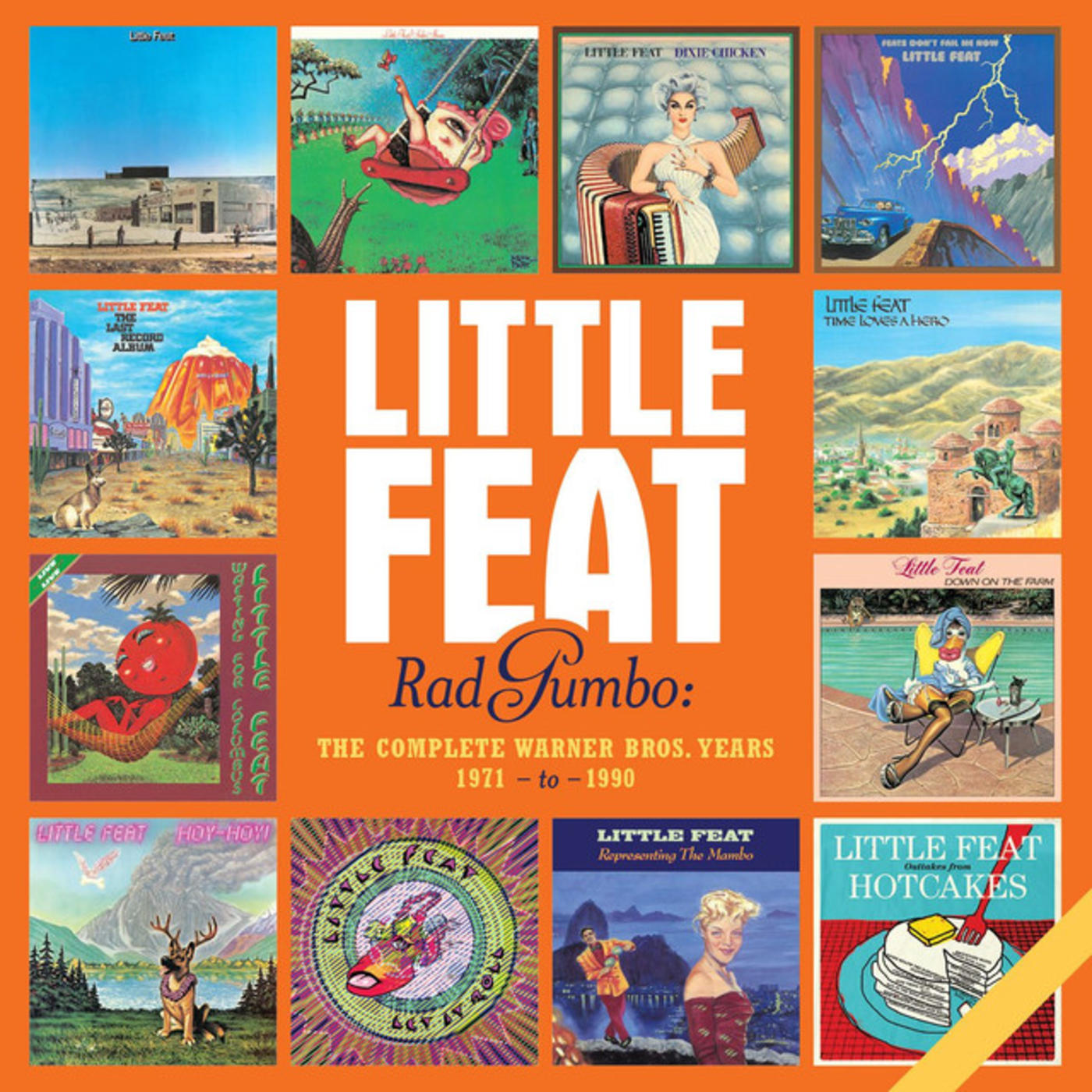

Put on your sailin’ shoes and prep your stereo system accordingly, Rhino’s served up a big helping of Little Feat. In conjunction with the band’s new 13-CD boxed set, Rad Gumbo: The Complete Warner Bros. Years – 1971-1990, founding Feat member Bill Payne was kind enough to hop on the phone for a nice long chat and spend some time reflecting on the band’s lengthy career on the label.

Rhino: How did you and Lowell George first cross paths?

Bill Payne: I was up in Santa Barbara…well, to be specific, I was just north of there, in Isla Vista, where the University of California, Santa Barbara was. I had a phony credit card that someone had given me. There were two labels that I could call: one was Bizarre, and the other was Straight Records. They were both Zappa labels. Naturally, I called Bizarre – though I’m sure the same person would’ve picked up the phone for both – and, you know, here I was on the street, basically, saying, “Uh, I play keyboards…” [Laughs.]

It took several calls to sort of get this person, this lady on the other end of the line, to take me seriously enough – or maybe she felt sorry for me – to put me in touch with Jeffrey Simmons, who was with a group called Eureka, which was one of the bands in Frank Zappa’s stable. I finally did meet Jeff at the Tropicana Hotel on Santa Monica Boulevard, and Jeff said, “Oh, well, I play keyboards, too, and this might kind of destroy what I’m doing, but there’s this guy Lowell George that I really think you ought to try and reach.” So Jeffrey put me on to Lowell.

By all accounts, the formation of Little Feat seems to be tied to Lowell being fired from the Mothers of Invention, but the specifics have gotten a bit blurred. For instance, it’s been said that Frank Zappa fired because Lowell played him “Willin’” and Zappa said that it was so good that he needed to be in his own band, but it’s also been said that Zappa fired him after hearing the song because the lyrics included drug references. There’s also a pretty awesome story which suggests that Lowell was fired because he played a 15-minute guitar solo without ever plugging in his amplifier.

[Bursts out laughing.] Wow. That’s a good one. I’ve never heard that one... although any of them seem credible! But I’d say that it’s definitely the first two you mentioned. The drug references, first and foremost, I think that put Frank off. But Frank dug Lowell. I mean, he liked him, so he knew “Willin’” was a good song, and that Lowell really ought to be putting his talents elsewhere, and if Frank could help on that, then that’s what would take place. I wasn’t exactly sure in the beginning how much or what Frank was doing behind the scenes to help us, because…well, we took a year before we wound up at Warner Brothers, for example. We went through a lot of different people to try and get the right fit.

Richie Heyward and Roy Estrada had both played with Lowell to some extent before you joined them. Did it take long to find the groove between the four of you?

Well, the first sessions I did with Little Feat – or with Lowell, at any rate – were down at TTG (Studios), with a band that I guess was called The Factory, with Martin Kibbee, Richie, and Lowell. I didn’t know that, though! My version of that particular group of recordings was that we were just going in to make some demos. But as for “the four of us,” the lineup that was on the album, that didn’t happen ‘til much later. We went through…oh, I’m gonna say between 14 and 20 bass players the first year.

So you’re saying that Little Feat was the Spinal Tap of the ‘70s L.A. rock scene.

Oh, God, we sure were. That movie scared the hell out of me…‘cause it was so accurate! [Laughs.] But, yeah, we went through a lot of bass players. In fact, (future Little Feat guitarist) Paul Barrere auditioned to play bass for us, and there’s a famous story on that one, which I think is worth repeating: when Paul said, “Lowell, I don’t play bass, I play guitar!” Lowell said, “Well, that’s two less strings!”

When you look back at the band’s self-titled debut, do you think it’s representative of the band’s sound, or do you think it’s more of an anomaly?

Well, it was what we sounded like back then. The material was very difficult to peg and to go, “Yeah, they sound like this.” It’s still quite unique. It had influences of the Mothers, the Band, Leon Russell and a bunch of other things. I didn’t sound like Leon, but I tried putting that rasp in my voice and all that stuff. It was just this unique blend of Americana music, essentially. And I was quite pleased when Bud Scoppa wrote reviews on songs from the record for Rolling Stone – he did a review of “Hamburger Midnight” and…I want to say he also did a review of “Strawberry Flats” – and thought we were brilliant. I thought, “Hey, that’s cool!” [Laughs.]

Was it challenging to write songs with Lowell?

I think it started off in a pretty straightforward manner, but it became increasingly difficult from there. And I don’t blame the guy: he wanted to do his own thing. One of the songs that we wrote which is representative of a good match is “Truck Stop Girl,” which the Byrds recorded. But after that… That’s why I did “Tripe Face Boogie” (from Sailin’ Shoes) with Richie. There’s very few songs I wrote with Lowell thereafter. But by the second album, with “Easy to Slip,” that was just pitched down the middle of the plate, trying to create a single, and it’s a wonderful song, obviously, but… [Trails off.] Lowell’s writing… I thought he was really, really great, but I was just trying to catch up. I’d never written songs before, so for me it was a little more difficult to kind of figure out where I was in the scheme of things. But I had a lot of chords at my disposal, and I was aggressive enough to take care of my own territory, and…that’s what happened.

Sailin’ Shoes was the first – but certainly not last – Little Feat album with artwork by Neon Park. How did you guys first meet up with him? Was it the Zappa connection?

It was. There was an album of Frank’s called Weasels Ripped My Flesh, and I think that was the time period where Lowell met Neon. And, God, what a find that was. [Laughs.] Neon Park was like the fifth Beatle, as far as I’m concerned.

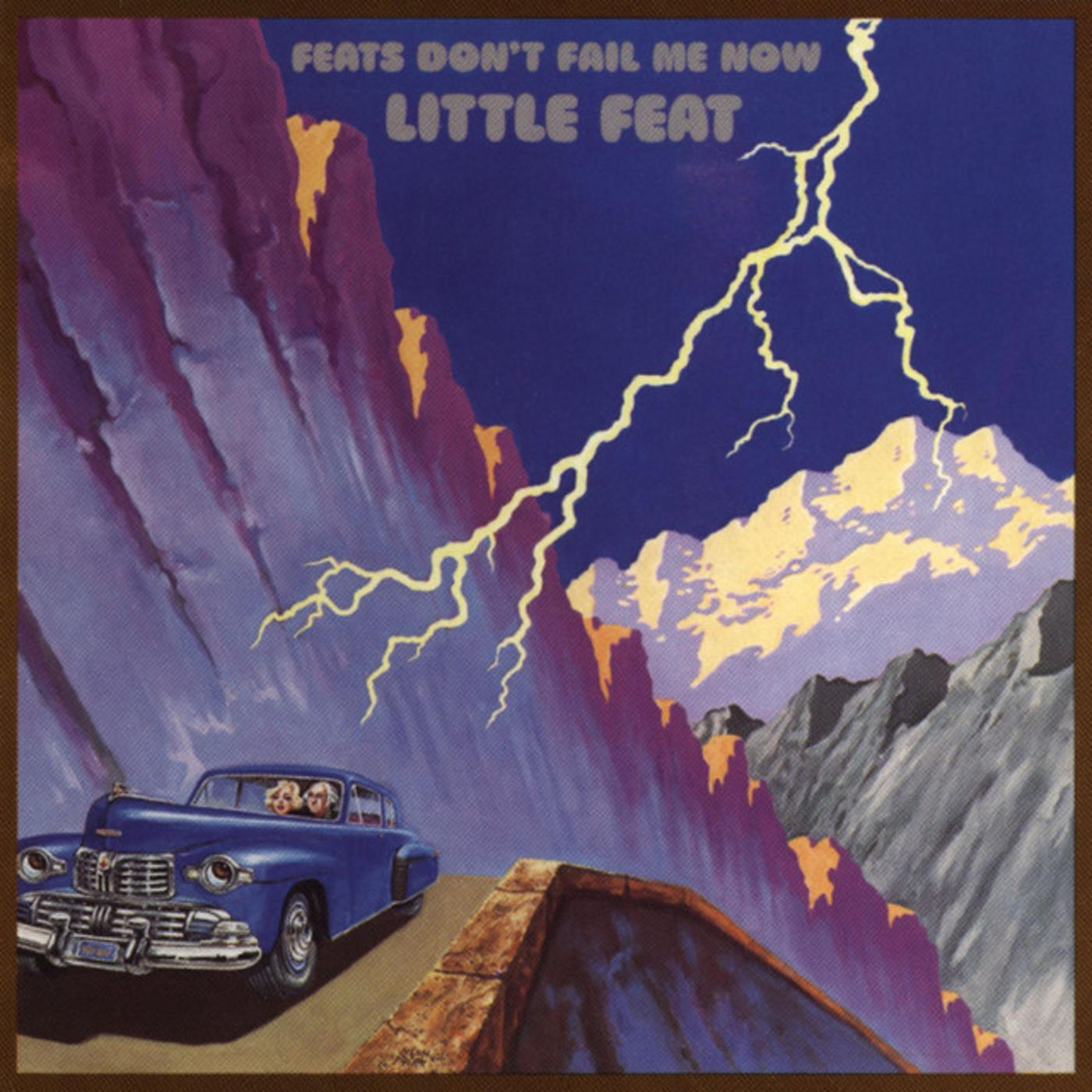

Do you have a favorite of the album covers he did for the band?

Not really. They all spoke and encapsulated visually what we were and what we were doing, and I thought that was the brilliance of the guy, being able to do that. He’d sit and talk to us and go, “So what are you going to do now? What’s happening?” If you look at a cover like, let’s say, Feats Don’t Fail Me Now, I’d go, “All right, man, what is this? I get the fact that you’ve got the mountain there, and the car’s either going uphill or downhill, you’ve got the lightning in the background, so we’re presumably coming out of some tough or heavy weather, but…what’s the significance of George Washington and Marilyn Monroe?” And he’d go, “Bill, this is rock ‘n’ roll, man: riches and bitches!” [Laughs.] And I’d go, “Oh, okay, right!” And on and on it goes. There’s a lot of stories to go with those covers.

But Neon was a dear, dear, dear friend. You know, years later I got him to help us write “Representing the Mambo.” [Quoting.] “The new crowd says I remind them of Frank / Who died of excessive nymphets / In Barcelona.” That was one of his lines. And so was the bit about high-heeled stilettos (in “Down in Flames”). So he could write as well as paint.

When you look back at Sailin’ Shoes, what comes to mind?

You know, I think when you hear that record and listen to the growth of the band between the Little Feat and Sailin’ Shoes, there’s so much more maturity in the record. We got a little bit more used to recording. I think Lowell’s chops as a writer – and mine, too, with Richie – were starting to kind of blossom, and…it put us on the map. Not sales-wise, but as a group to be taken seriously. Listen to Lowell’s guitar on “Easy to Slip,” for example. I mean, it’s just some great stuff, ‘cause you can hear he’s combining a really good acoustic guitar sound with…well, I don’t know what he was using as an effect on his electric guitar, but it was really, really good. I think it still holds up.

Do you remember what led to the decision to re-record “Willin’” for that album?

I don’t. Having heard the first version, though, I think what happened was that we started playing it and…well, okay, I’ll put myself into it: I think the first version was kind of a Country Zeke and the Freaks version. [Laughs.] That was one name Lowell considered using for Little Feat instead of Little Feat. It was almost a caricature song. And when you put the piano on it the way we were playing it later, it brought the real thing into it. I listened to a lot of Conway Twitty back then, and to me it was… I don’t know that it was a joke – and I may be over-reading here – but I do feel that “Willin’” really came into its own when we made that switch from being guitar-oriented and put that piano in there. It elevated it.

There’s a general perception that Dixie Chicken was the first album where Little Feat was firing on all thrusters as a band. Do you feel that way?

Well, I think that it was just a different thrust. One of the things that Lowell and I talked about in the beginning was keeping a rather open attitude to who might be in the band. So if we wanted to add horns, if we wanted to add another guitar, if we wanted to do this or that… It was a vehicle to play a lot of different types of music, which I really thought was a great idea. And that’s what I wanted to do anyway, ‘cause why limit yourself to a certain style? We didn’t even know what our style was! [Laughs.] That’s what you do as an artist: you try and figure out who you are. But if who you are is… Like, it’s cool if you’re just playing the blues. If that’s what you’re acclimated to do, there’s no harm, no foul in that. But blues was part of what we were doing, country was part of what we were doing, rock was part of what we were doing, as was R&B. We were designing it up and down from there, and it was a wonderful palette to paint from.

So we had Kenny Gradney and Sam Clayton, both from Delaney and Bonnie’s band, and we had Paul Barrere, who –as I said – auditioned to play bass for us, but he’d known Lowell from Hollywood High. Paul and his brothers went to Hollywood High before most of ‘em were thrown out. [Laughs.] So there was a history with those cats, and…I thought that was cool. The New Orleans thing just sort of came in the door through Clifton Chenier, Professor Longhair, and some of that. But Kenny and Sam were both born in New Orleans. I was born in Texas. We weren’t usurpers of anything. We were taking influence, which was… The core of what made Little Feat was and what it is today is the ability to absorb influences outright or to mix ‘em in with other influences and come up with material. It’s pretty much that simple.

So we weren’t, like, the stewards of anything. We weren’t, like, “Well, here’s Howlin’ Wolf, so we’re gonna sound just like Howlin’ Wolf.” We did some of that, sure. But the piano part for “Dixie Chicken”? If you listen to the first Howlin’ Wolf record (Moanin’ in the Moonlight), the song “How Many More Years,” there’s a piano line that’s on the original Howlin’ Wolf record, and that descending line is on “Dixie Chicken,” except it’s not played the same way. To put it in musical terms, I shifted a third – an E and a G-sharp, let’s say – and I made it a B and a G-sharp, but over an A. So it’s, like, an E over an A chord. I don’t know if you’re a musician. If you’re not, that might not make any sense to you at all. [Laughs.] Anyway, I’m not saying it’s an iconic keyboard lick, but people have told me that. I just thought it was a nice little twist on what I heard on “How Many More Years.”

In regards to the open attitude about the people playing in the band, the same seems to have gone for those singing with the band as well. The backing vocalists on Dixie Chicken are pretty phenomenal: Bonnie Bramlett, Danny Hutton, Gloria Jones, Bonnie Raitt…

Yeah, it was a good mix of people! You know, that was another thing I talked about in the beginning: what kind of band did we want to be? And Lowell and I both envisioned Little Feat – with luck! – to be a band that would be well-known within the musical community. We weren’t necessarily looking to be a band that was across-the-board well known, but we certainly wanted to be influential ourselves as well as be influenced by others.

When you look at the band’s back catalog during the years with Lowell, is there a definitive album from that era in your mind?

I think the one for me that was the most fun to make was Feats Don’t Fail Me Now. You know, it’s got “Rock & Roll Doctor” on it, it’s got “Oh, Atlanta,” etcetera… There were just some really wonderful songs on there. It was also a really good period for us. We met Robert Palmer, and Robert came in. We met Emmylou Harris. My first wife, Fran Tate, she came in with Emmylou to see George Massenburg when we were in Maryland. We did that one at Blue Seas Recording. Inara George (Lowell’s daughter) was born on July 4 back then, so that was really cool. Obviously, the record people look at – and I love it, too – is Waiting for Columbus. That’s a definitive record. But those songs that were recorded for that, quite a few of ‘em – not all of ‘em – were from Feats Don’t Fall Me Now.

Is there any performance on Waiting for Columbus that leaps to mind as just completely blowing away the studio take?

“Fat Man in the Bathtub.” It’s amazing. The drum sounds on that are just incredible. When it comes up to that part, “Hey, lordy, join the band,” and the crowd noise gets louder and louder and louder, and then Richie breaks into that… I mean, the hair on my arms was just standing straight up when I was listening to that in the studio. [Laughs.] I knew at that point – and how could you not not know? – that this was a powerful, powerful record. God, it’s just amazing to me how good it sounds, the performance… But, I mean, we were always more of a live band. That’s probably the most succinct way to put it.

We did some work on that record, though. Not on all of it, but I don’t hide the fact that we… [Hesitates.] We kept a good deal of what we played, but if there were fixes to be done, screw it, we went in to redo the guitars, and we redid a few vocals here and there. But for the most part, it’s a live album, and it’s a damned good one. Little Feat was never a band that adhered to rules all that easily, y’know? So if people go [In a mocking tone.] “In order to have a live album, you must…” Well, you don’t have to do anything. You can do whatever the hell you want. It’s a recording. It’s a picture of a place in time, but if you want to fix something, then go on and fix it! It’s still you playing it! [Laughs.]

I still maintain that attitude. I don’t do things out of spite to anything, or thumb my nose at a genre, let’s say. But I’m not going to let the genre handcuff me, either. And I think some people do, and they do it out of respect, but the ones that are the most dogmatic about it… Look, let me just say that I’m not going on this bent because of Waiting for Columbus. I don’t know that anybody’s ever really said, “Oh, it’s not a live record, because they overdubbed on it.” I don’t think anyone knows or cares! But in general… Like, on “Representing the Mambo,” people said, “Well, that’s not a mambo beat!” I said, “Well, I’m not writing a mambo song, either!” [Laughs.] It’s one of those kinds of things. Or if you do some sort of country music hybrid, like “Strawberry Flats” or “Truck Stop Girl” on the first album, which have country elements in it, they’re not classic country songs, you get people going, “Well, here’s the way country music’s supposed to sound!”

In regards to Little Feat’s blending of genres, The Last Record Album was the first time you and Paul started to incorporate somewhat of a jazz element into the music, something which Lowell apparently didn’t exactly love.

Well, yeah, he wasn’t really a jazz fan. I remember in particular he had a real problem with “Day at the Dog Races,” from Time Loves a Hero. But, hey, he said, “Go in some directions and do some stuff you’d like to do,” so we did! But one of the first albums I looked at at his house was one by John Coltrane, so he wasn’t unfamiliar with jazz. He certainly knew what it was, and he might’ve liked… Well, I don’t know what he liked. Jazz is such a huge topic, you know? But I don’t think he liked jazz fusion…although I would’ve liked to have heard him say that to Joe Zawinul of Weather Report. [Laughs.] But that’s okay. To each their own.

Can you offer some insight into the end of the band?

I stepped away from the band, Lowell was still in it. I wanted to produce one of our records. I wanted to get involved in the record we were making at the time, which was Down on the Farm. He said, “No,” and I said, “Well, I don’t want to be in this band!” And we had a long talk about it, and I kind of gave him a rundown of what I thought he was doing not only to the band but to himself and to his family…and to his credit, he allowed me to do that. But shortly thereafter he went out on tour, and that was it. So part of what I felt was, “God, you’ve got to be very careful what you ask for!” I ended up helping to produce the record…but without Lowell. And…it was a tough thing to go through.

How do you look back on the album now, given that you had to complete it in the wake of Lowell’s death?

Well, as I say, it was a very difficult record to complete because of that. Richie was in the hospital, laid up after yet another motorcycle accident, so he wasn’t there. We did a benefit for Lowell at what was at the time called the Forum, in Los Angeles, and that money was going to Liz George and the kids. There were just a lot of things going on, and…I don’t view that record with any particular joy. It’s more sadness. In my part, anyway. But the song “Down in the Farm,” I love that tune. It’s always been a great tune to play live. It’s just… I just wish things could’ve been different. But they weren’t.

That was one reason I wanted to put out that record Hoy-Hoy! Because I thought there were some things that needed to be said. “Gringo” was one of ‘em. “Over the Edge” was Paul’s contribution. And then there were some things (from the Lisner Auditorium shows) that weren’t on Waiting on Columbus, and then were a couple of things which were – quite frankly – bootleg tracks that we took from a fan. And when I told Mo Ostin that, his eyebrows went up, but I said, “Mo, we’re gonna make some money off of it for a change!” He said, “Oh. Okay.” [Laughs.] I love Mo Ostin. He was just a true music aficionado and a really great record president. I mean, this guy… He’s one of my heroes.

When Little Feat got back together and released 1988’s Let It Roll, Craig Fuller – late of the Pure Prairie League – was handling vocals? How did he come to enter the mix?

With us on the very last tour Little Feat did with Lowell, which was in either ’78 or ’79, were Fuller and Kaz. Eric Kaz and Craig Fuller. Eric Kaz and Libby Titus wrote “Love Has No Pride,” which is a beautiful song that Bonnie Raitt did, and Linda Ronstadt as well. And Craig wrote “Amie,” which is a really fine song, too. But I liked the guy. I just thought, “You know what? Let’s see what he can do.” So we brought him in, and he was wonderful. A really good songwriter and a wonderful singer.

It wasn’t until almost a decade after Lowell’s death that you revived Little Feat. Did you have any hesitation about continuing on without him?

Well, he died in ’79, and we were contemplating bringing this thing back in ’86, I think. And I had to go out on a tour with Bob Seger, and Fred Tackett was a part of that tour, and…to answer your question, I had plenty of trepidation about it, but only in the sense that we hadn’t written one tune yet. [Laughs.] And we weren’t sure who was going to be in the band, in terms of, y’know, you can’t take Lowell’s place, but you need somebody in that slot. I thought we did, anyway. So all these questions had to be resolved in my mind. I had everything lined up – label, accountants, lawyers, management, the whole thing – but I said, “If we don’t write the right songs, or songs that we can listen to not only within Little Feat’s catalog – because we’re up against ourselves here – but also sandwiched up against the music of anyone else we like, then we don’t deserve to give this another shot.” Because the last thing I wanted to do was to impair our legacy…and that’s for us. Plenty of people have looked at the reconstitution of Little Feat and said, “Well, without Lowell…” You know, that kind of thing. Other people came and went, “Man, it sounds great!” So it was a study in conviction.

Once during an interview, Ben Fong Torres asked me, “What were you thinking?” [Laughs.] And I looked at him and laughed, and I said, “Are you talking about Representing the Mambo?” He said, “Yeah!” I said, “Aren’t you interested in how I knew what you were talking about? Look, Ben, I wanted to prove that we could turn left on a dime.” When I realized we were a little too artsy with it – I’m not denigrating the song at all, but just in terms of Warners and public perception – I said, “If we’d called that record Texas Twister, I don’t know what would’ve happened, but I’d bet we would’ve probably been okay in terms of a good follow-up to Let It Roll. Neon even painted another cover for it. He says, “Yeah, but do you think that would’ve helped?” I said, “Yeah, I do. Perception is everything.” Perceptions and expectations. So I’m glad we put it out as Representing the Mambo. But I knew enough to think, “Gee, what if we’d done something different?” and Neon indulged me on that, which I thought was quite cool.

For the critics who might’ve been less pleased with the album, you certainly gave them a perfect straight line with a song entitled “Those Feat’ll Steer You Wrong Sometimes.”

That’s for sure! But that song was originally called “Ol’ Hank’ll Steer You Wrong Sometimes,” as in Hank Williams, Jr., but I couldn’t call it that because – and I think rightfully – his handlers said, “Look, he’s in enough trouble. We don’t need to have you do that!” [Laughs.] But I think he’s a great guy, and a great model for that tune.

What happened was, I got a traffic ticket in Texas following a James Taylor rehearsal up in Dallas. I went down near Waco to visit my folks, and on the way back I got a speeding ticket. The officer said, “Son, you was goin’ about 80 miles an hour.” I said, “Well, gee, officer, I was listening to Hank Williams, Jr., and the speed just slipped my mind.” And he goes, “Son, ol’ Hank’ll steer you wrong sometimes.” [Laughs.] You can’t make this stuff up!

Is there any particular album from the Warner Brothers era that you think of as underrated, that people should consider reevaluating?

I think all of ‘em! [Laughs.] Well, in terms of public view, which is why Warners is putting this thing out. I think the only one that really stood above ground and sold quite a few was the live album, Waiting for Columbus. But…I don’t know, I’m being somewhat facetious in that comment. You know, people go, “Oh, don’t you think you ought to be in the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame?” and all that kind of stuff, but that’s not we did this. That’s not why we’re doing it. I look at the Hall of Fame as the last brick in the wall, if we ever get in there. And then now there’s a debate about how, if Little Feat is inducted into the Hall of Fame, should it just be Lowell and the original band? I’ll say this…and I haven’t said it publicly, but I guess I will now: that is not the issue. That is not what Little Feat is. Little Feat is a concept that is bigger than us at this juncture, and what it has to do with is musicianship, with songwriting, and with influences. And I think we honor Lowell, or we try to, every time we hit the stage or write.

I just turned in my 18th song with Robert Hunter two nights ago. And I write with Paul Muldoon, the Pulitzer Prize winner poet who’s the poetry editor at the New Yorker. Jeff Bridges and I and John Goodwin, a friend of his since fourth grade, we’ve written a song, and I’ve written two more with John. I write with a lot of people, including Tom Garnsey here in Montana. Will they be on a Little Feat record? If in fact Little Feat continues, some of them will. That’s what the experiment always was. Of course it’s about personality, as it always should be, and Lowell George is rightfully one of those guys people look at and go, “My God, this guy was bigger than life.” He was. And so was Richie Heyward. Richie’s one of the world-class drummers of all time. But you’ve got Gabe Ford in there, too, who’s turning some heads. A dear friend of mine from the Midwest, Steve Wells went, “At first I couldn’t get used to Gabe, but then I shut my eyes and listened to the music, and I went, ‘Oh, my God, that guy is great!” They’re used to watching Richie flail around up there with all arms and legs and his movement, and they don’t play the same way, but what was the impact? The music. I said, “Well, Steve, you did a very smart thing: you listened.” [Laughs.]

Somebody – not me, but somebody – will see where Little Feat and this music winds up, but when people have asked me, “Well, do you think this stuff will last?” I just say, “Well, I don’t know…but Beethoven’s done pretty good!”